Introduction:

Reading this excerpt reminds me of walking the cobblestones of New Orleans when the moon is a coy crescent guide. There is a feeling there I have not found in any other American city. Some vapor rises through the cracks of the stones, up, through the bones and around you.

Your thoughts drift beyond form, cause, or morality. You are art, putty, circumstantial to the vapor. Everything pretty is possible, music and dance, the serendipitous is the guest of honor, but so is the violence, the shadow kings, the ghosts of the history, of the city.

Reading this excerpt I feel like I walk along those stones again, where everything, everything is possible, where “God is only on the ceiling” and “not all good guys have class,” and “sleep comes the length of a desert palm’s long, afternoon shadow,” as “Beelzebub and Gabriel throw dice honed from a hanged man’s teeth.”

Here, wherever it is, “light clumps into “shunts,” “the night wanders,” and “roads… moan against angry boots.” Everything here is living, or dead – a negotiation between ether and bone, mediated by poetry — and the momentum of everything, its conversation, is the odd, carnal and lucid meeting of strangers as below them the moon turns the old stones blue.

Nikita Nelin

Professor, Poet, & Novelist

“Fluorescent lighting is…garish.” Rice looked up through sunglasses.

“Then turn it off.” Kabal hated it, and barely less – Rice.

They’re in a dentist office with Miss Dixie kidney-deep in smack. “I like it,” she says.

“We just kill her,” Mabel spits and glares at Miss Dixie. In a guttural holler-accent, “Because he will kill us.”

Rice reclines in the pleather-and-steel dentist chair. He stares at the screaming fluorescence overhead, “He’ll try.”

The dentist, two nurses, and a UPS deliveryman lay dead, in a heap against the shuttered office front doors. The four of them have the place a full 48 hours before the first appointments show up knocking Monday morning. Enough drugs to keep Miss Dixie sideways, Kabal less obsessive, and Mabel quiet. Rice needs the lights.

Rice, the Rasputin from Baton Rouge,

plays guitar while heroin cooks.

Filched spoons, the underside (the cereal-eating half),

candle-licked. There’s nothing clean in the room.

The boss is

with Miss Dixie:

The burlesque-beauty

swept up and pulled in by war.

…

Tell me about my nightmares, Miss Dixie asks,

and Rice does. Tenuous is patience

in the whispered lulls and temper tantrums.

Dixie is a dirty needle’s contents.

Feeling cosmic-sexual, she bites Rice

into speaking their nightmares

from a hollow wound

in his forehead.

Out of the mouth of his dark third eye,

“Below the Bible Belt,

Atlanta’s shadow gals bring good work with them.

Water was wine when it arrived.

The deacons are mad,

their hymns

pounded into a Sherman Neck Tie.

The meek only inherit

a hard time.”

Those who come from

Nowhere are written

on skin Old Scratch scribbles

to keep track of bad children.

Rice, havoc has no starting point.

Rice retells his histrionic business

that bested Blue:

“God is only on the ceiling.

Not all good guys have class.

There is beat-out hope

but little else not wholly wiped from Earth’s ass.

Blue did always angle to burgle

redemption by murdering

by a wizard.

He hit a wall, thinking

of a way to keep living.

In the deep recess of her time-healed track marks

Miss Dixie giggles.

She hasn’t stopped

since trying to make sense

of why Blue won’t lose her.

“False hope is the highlight of nightmares,

the sight of a web’s slow unweaving,

the sound of bamboo split to its pale root.

These are themes from Blue Crawford’s

Hallelujah.

He sings them each day,

alone, to hold onto humanity.

It signifies nothing.”

…

Kabal predict who will survive

the fatal joie de vivre of their Rapture.

They’ll all slouch towards the sunset all the same.

Sleep comes the length of a desert palm’s long,

afternoon shadow.

Mabel see herself joined

to a coroner’s report unfiled

because the corpse is unaccounted for.

She isn’t a sociopath about

being mankind’s language

of something Higher,

to express a place much Lower.

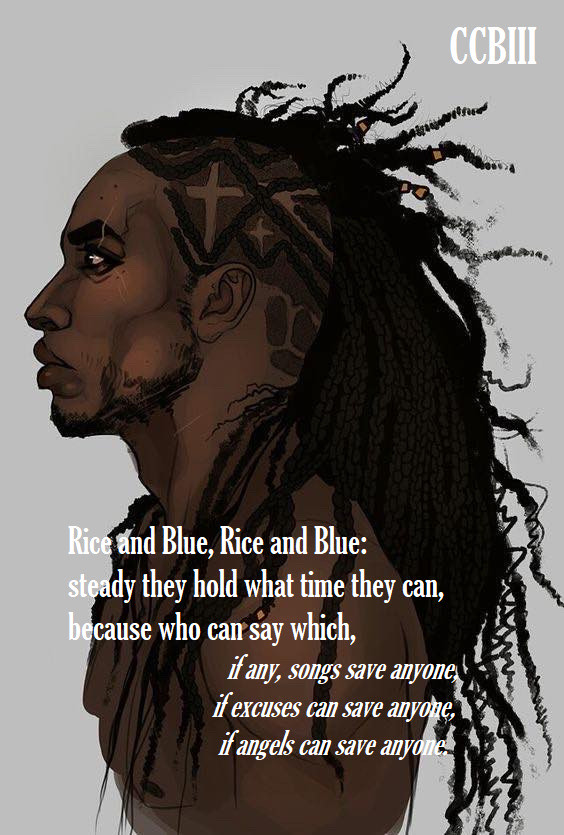

Rice and Blue, Rice and Blue:

steady they hold what time they can,

because who can say which,

if any, songs save anyone,

if excuses can save anyone,

if angels can save anyone.

An owl screeches, a sudden shunt of light,

and Mabel’s superstition cracks,

bear-armed in a circle of salt,

“Gimme me voodoo, Rice.”

Rice plays with the waist of Miss Dixie,

but he doesn’t do well in the doing of it.

She is another tattered tall tale kept

along an unseen edge.

She is his haunting, an epistle Homer

wouldn’t hammer down.

Rice doesn’t trust Mabel with voodoo.

…

Cowboy Crawford would do better to awake from his current,

crying, standing ovation,

and into another, dirtier comedy of errors.

Maybe the shriek of cavalry on the horizon

does more good than Descartes’ Circular Idea of Being,

Milton’s lost paradise, leading Satan in Heaven,

or Pompeii brushed off and pieced back together.

Friends survive and stand tall in the Experience.

His momma would settle for

any-other-way-of-life.

Not the honky-tonk where Blue is half owner,

where Beelzebub and Gabriel

throw dice honed from a hanged man’s teeth

to enter Earth through Averno.

As night wanders into day

(curious, unbridled, and insensitive),

Aries prods the psychopathic Rice, the snake oil salesmen

to bare his skin, brandish its blades too-long unused,

and take up their poisons against Blue.

The Cowboy no longer cleaves to Miss Dixie.

Rice walks the same, long roads that moan

against angry boots.

On top of untamed ground,

Blue sings Johnny Cash songs

that sound better

than Jesus Loves Me.

Cowboy Crawford heads

home to Lexington

where the weather makes more sense.

Rice already burned it to the ground.