Abandoned tracks snake through the woods up by Ellijay. A long spot where there ain’t hardly wind, and the air is heavy with dirty, sweet smells that thwack the back of your mouth and sting going down. Chunks of lignite spot the limestone ballast between the ties and, on either side of the tracks, the jewelweed and mayapple have encroached—in some places right up to the steel.

Abandoned tracks snake through the woods up by Ellijay. A long spot where there ain’t hardly wind, and the air is heavy with dirty, sweet smells that thwack the back of your mouth and sting going down. Chunks of lignite spot the limestone ballast between the ties and, on either side of the tracks, the jewelweed and mayapple have encroached—in some places right up to the steel.

Far enough down the tracks, there’s a tumble-down church aways-off but not far enough it can’t be seen through the trees if you bend and squint. An odd place for a house of God, and maybe the congregation thought their hymns and prayers would get to Heaven quicker if they sung them onto boxcars. They might have picked up serpents in frenzies of ecstasy, mean old copperheads whose scaly ancestors still sun themselves on the tracks in places where the sunlight stabs through the canopy. How many serpents must have lost their heads back then?

These days, you could sit inside that little old church and listen to the chirruping tree frogs all day long, the woodpeckers’ ratta-tatta, the snap of underbrush when a whitetail walks through. The rumble of progress has gone the way of dead trees all through these woods, ate up by toadstools and termites. Same for the sound of holy songs. You’ll feel, pretty quick, like a small thing, a mute little bug, if you stay more than five minutes. For added effect, close your eyes.

Paul Luikart

Educator, social worker, author, poet, & painter

Chattanooga, TN

…

“Men are so quick to blame the gods: they say

that we devise their misery. But they

themselves- in their depravity- design

grief greater than the griefs that fate assigns.”

― Homer, The Odyssey

“Your mother will not condone this,” Father Hammer said.

Sword and Shadow stood off alone, dark eyes scanning, scanning, scanning.

“Momma understands me,” Blue Crawford murmured, more as a prayer than a statement of fact.

Father Hammer rubbed his hands together in a motion like washing off deep stains, “Understanding you ain’t approval, Blue.”

…

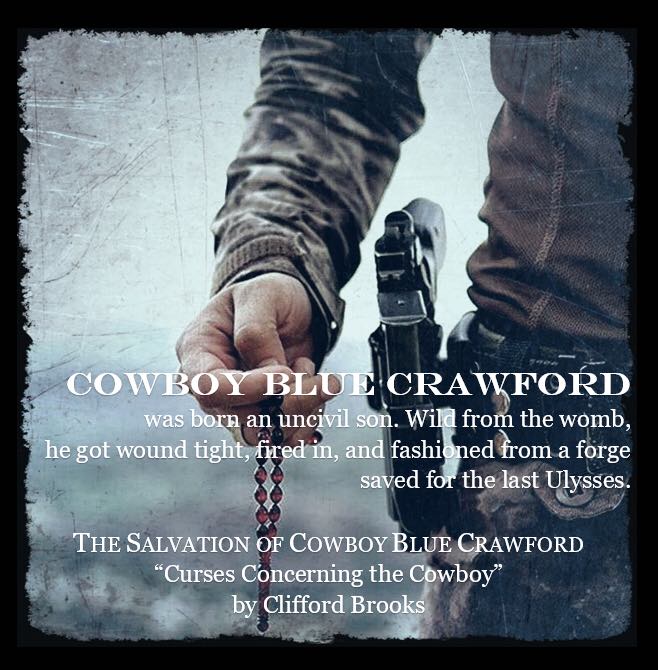

Screams, screams, and again – that silence.

Fitfully sleeping in a hopeful crib,

his father called him:

Blue.

“The boy will grow to be me,” hissed his old man.

Born an uncivil son, Blue Crawford, wild from the womb,

was wound tight, fired in, and fashioned from a forge

saved for the last Ulysses.

Natural fact: Blue hit the ground

and immediately found he spoke with

a slow-drawl-growl.

A good woman’s curse,

his mother’s innocence is laid waste, her. Heart is hurt by,

and hurting for, Blue.

The torture she learns to endure. Sure her boy

exists not for death, but in a saint’s employ.

A child can keep his momma away from pain

except for this bloody brand he made.

…

Lily locks her hand over Blue’s wrist, “I know she’s proud of you.” She grips him tighter to bring him about. “She knows you won’t fall in.”

Blue is grounded and hounded to be present, “I am aware, sugar.”

…

Forty years ago, the South sang about a son his momma

still speaks of

in spite of her shame. Do not toy with her hold

on her bold belief Blue will prove his worth to her

(and you).

The men in Crawford’s brood

find themselves more

than a little less, sewn up in self-interest.

That, over time, blends with the need to pretend

they can love others.

His prophesy was found in a tomb opened beneath a murderous moon.

Cowboy Blue is a child on whom

the whole world is laid upon. Coaxed up by Creole old religion,

stone got rolled away. Blue’s feral talents

and hoochie-coochie habits aren’t approved

by priests or zealous abbots.

Yet, Uriel

let him have sight:

The light – the scent of it.

Since his first steps, Blue’s jeans have been held against his hips

by a belt buckle etched in the effigy

of Saint Anthony. A small, brown Bible

is tucked in his

vest pocket.

The meat of the matter is that he too easily mastered

the ability to cheat a poisonous youth.

Those years – yes, a bit misspent –

did not leave him with the horrible scars

made from settling, solitude,

or prison bars.

Cowboy Blue isn’t lashed to the jaded stone

of a loner that’s lived too much.

There is no, real “alone.” It’s a matter of perspective.

Life can be radiant or barren prairie.

Blue’s luxury is bought with laundered lira

he invests to make the past less present.

Blue could consistently squeeze enough from his savings

to make it to another city.

(Maybe Miss Dixie would hide him

a hint in it, or in the next,

or in the next,

or the next.)

…

“You make me, me. You saved me. I will never leave unless I am taken,” whispered Ms. Dixie. (Lying, Ms. Dixie.)

“You were never mine,” Blue mutters in a weak hold.

…

Baton Rouge refused to release Miss Dixie’s secret.

Now in North Georgia,

Gainesville gave up his first wife’s ghost. A host of beleaguered friends,

and a flight of exhausted spirits waiver, sprint, tag-out/tag-in

then insist away the savage

instincts that inevitably

leak in.

You see,

New Orleans leaves love

strewn out like a train wreck. Its beauty is crazy.

Terror is a detail in a demon’s arsenal. Anguish is an aggressor’s

best cadence to keep up their cause for carnage.

Cowboys come through

to do the bad better men choose not to.

Without fear the flock

would think their faith in escape is true.

Iniquity is as weak as its stupidity

is infinite.

When Blue gets back to the bayou, his two rooms are right as rain.

Love is an elusive lie of want. This is a story worth telling,

because it is the cause

of why he (now) sleeps so soundly.