Song of Introduction:

After the God of this world

has turned his back on his creation

a sole cowboy leans a shoulder

on an apple tree

atop the highest cliff in an ocean of dust

and looks as far as the eye can see.

God’s turned back

casts a permanent solar eclipse.

My soul sees you

your soul sees me

better as one

than we are as three

Under the black sun

the cowboy plucks a golden apple

from a stringy branch and mumbles: “to destiny”

and sinks six teeth into its ripe flesh.

Blue, rest now for your soul is

Old, like the wind that carries the breath of our fathers,

sighing between the branches of a willow tree.

Deep, like the ancient rives that still run beneath the ruins

a place once called home.

Dark, like the spirit inside all of us who become addicted to life,

holding on with a firm grip, and never letting go.

Be gentle, cowboy,

when you knock the dust off your boots,

with it carries the bones of the dead.

How much dirt does it take to make a body?

How much of a person can be salvaged from the

Great Fire after the embers have begun to cool?

Geb, son of the earth,

lets out a low laugh. Rocks tumble

and feel the thrill of gravity

finding new ground to rest.

The apple falls to the earth and Blue

makes his way down the mountain.

Author // Publisher // Editor

…

Alone, alone, all, all alone,

Alone on a wide wide sea!

And never a saint took pity on

My soul in agony.

The many men, so beautiful!

And they all dead did lie:

And a thousand thousand slimy things

Lived on; and so did I.

I looked upon the rotting sea,

And drew my eyes away;

I looked upon the rotting deck,

And there the dead men lay.

I looked to heaven, and tried to pray;

But or ever a prayer had gusht,

A wicked whisper came, and made z

My heart as dry as dust.

I closed my lids, and kept them close,

And the balls like pulses beat;

For the sky and the sea, and the sea and the sky

Lay dead like a load on my weary eye,

And the dead were at my feet.

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Just outside of Cairo, incinerating inside a tent with his thaloc tied up, Blue couldn’t take his eyes of the little god’s trinket. An amulet hung around the deity’s neck. Its face shifted from man to fox and back with a clean, toothy grin that Blue found disturbingly peaceful.

“Take it, cowboy. I am tired,” the thaloc said, “The amulet anchors me here.”

“Tell me about it, Andy.” Blue couldn’t remove it, so he held it between his thumb and forefinger, “How does it work?”

The thaloc’s name is Andy. Not a particularly ancient or culturally-centric name. Blue doubted it, but “Andy” is easy to pronounce. There was no discussion on how it knows English.

Sword & Shadow caught the Egyptian demigod an hour before dawn. The silent samurai tied the child-sized foxy creature to a tent pole. Andy never struggled. He never called for help. Every so often Andy smiled at something over Father Hammer’s shoulder and then behind Lily’s legs.

“It gives you and your kin immortality. You can fly. You are haunted by angels and chased by evil men. Take it.” Andy pleaded.

“It won’t come off, Andy.” Blue pulled the jewel up, but the chain caught behind Andy’s head.

“Not while I’m alive.” Andy whispered.

Blue grimaced, “Not while you’re alive,” and with his left hand holding the amulet, his right pulled a Colt.

The pistol pressed flush with Andy’s head, he closed his eyes, and exhaled. Wind swept in and around the small gathering.

…

Blue Crawford’s longevity is morally unlawful.

Immortality provides a perspective that perpetually proves

there’s no longer anything to lose.

The cowboy becomes an angel’s brand of being awful.

Now, “officially,” vengeance is allowed to exist

as long as the to-be-deceased are ethically diseased.

The creed of Blue’s intent:

“I first spoke with Enoch

who told me about the thaloc.

The prophet confessed without its jewel

I am made with a waiting casket.

Once within me my ethereal feet

no longer trod

towards a God who allows my anguish.

Now, there’s no sense of time,

but a terrific taste to torture every

living

wretched thing.”

Blue imbued with dark light continues,

“Until heaven decides to debate and defend

the slaughter of innocent, intelligent kin,

the thaloc’s amulet will remain a stain

beneath my brutish skin.

I choose this unwinnable, millennial war,

before dying to discover nothing more

than the futility of celestial ambiguity.”

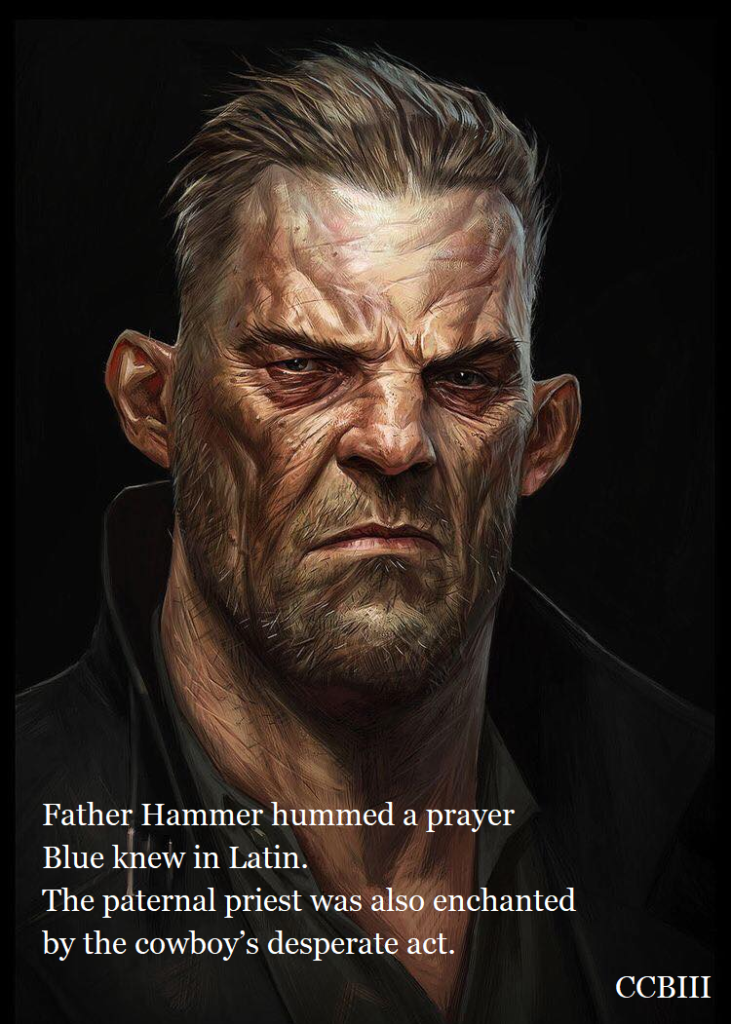

Father Hammer hummed a prayer

Blue knew in Latin.

The paternal priest was also enchanted

by the cowboy’s desperate act.

Hammer always on watch, now in stone

standing, casting a shadow

outside their hotel window.

“Sleep, you childish beast.

Let that lady believe that, maybe,

you cherish her smell and lips

more than her marksmanship.”

…

Father John Misty

makes his way around the turn table:

honey bear

ooooo-ooooooooooo…”

Cowboy Blue Crawford turns off the sad rhyme

and absently thumbed his pistols.

The weeping, throbbing chest

cracks and seeps

due to the emerald, imperfect crystal.

His Colts in their holsters,

he consoles her, but an ocean of it

isn’t enough

to contain her current of discontent.

Blue touches the talisman

charred into his chest.

An Egyptian, a last ancient,

a thaloc lost to the shrewd Blue.

The cowboy will forever croon, unable to die,

and under special circumstances – fly.

Rice, Azazel, and Mabel were tricky,

absconding with Miss Dixie.

Dixie: The mother of an American South.

Blue’s rage, they are the how, when,

and why.

Evil will not abide.

Blue’s family is his pride.

“Lily, don’t let doubt dig spines

in your spirit. I will unhinge hell

to have you happy.

Be still.”

But Lily still hurt.

To harbor a haunted man

sealed a deal she accepted

ages ago. Even so, no caring flesh adequately adapted

to the hollow

Blue holds onto.

Blue knew,

and it hurt him,

too.

“Baby Blue, you are one of the unspoken few

to be so shrewd and clever

that even the Devil

wants you to live forever.”

“What a difference a day makes.

Twenty-four little hours…”

A song for sweet Lily,

the tune Blue eases deeper into.

She deserves a serenade no less.

Out of the mess,

he now insists,

damnation will pay off.

They will both be (paid off)

in that bare-clawed basin,

and wash off the boring past

no longer wasted.

Lily dips her shape, a dancer’s, bartender’s leather,

she is pulsating

above the corruptible menace,

his double aorta, visceral pear

that pulses with a wendigo’s tearing

hunger.

Lily sings from the tub

where she can get sinless,

but never clean.

Wound in sheets wet

from sweat squeezed from between them,

Lily lets him sleep.

Nightmare-eaten, Blue is brow-beaten,

by memories of Miss Dixie.

Lily prays for a soothing ending

before his malaise

makes a malicious scar.